Biography:

CURTIS LEE MAYFIELD (b. June 3, 1942 – December 26, 1999)

by Mark Allred

You are right. The music of Curtis Mayfield is not considered JAZZ. Yet he has influenced those who are considered jazz. In fact he has influenced many a genre as can be witnessed by the successful cover songs and numerous tribute albums released by other artists. Certainly he was more established as an African-American soul, R&B, and funk singer, songwriter, and record producer. Curtis Mayfield is also remembered for his 1960s Mo-town sound with The Impressions and his anthem style music during the Civil Rights Movement and today is regarded as a pioneer of funk and of politically conscious African-American music. To top it all he was also a multi-instrumentalist who competently played the guitar, bass, piano, saxophone, and drums. His solo career peaked commercially and critically when he composed the soundtrack to the “blaxploitation” film Super Fly. The whole soundtrack stood alone as a musical release with or without the movie. Super Fly sold over one million copies and was awarded gold discs by the R.I.A.A (Recording Industry Association of America). Mayfield’s lyrics often consisted of somewhat gritty hard-hitting commentary on the state of affairs in black, urban ghettos at the time. Bob Donat wrote in Rolling Stone Magazine in 1972 that the anti-drug message on Mayfield’s soundtrack is far stronger and more definite despite what may be portrayed in the film. Along with Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On and Stevie Wonder’s Innervisions, Super Fly ushered in a new socially conscious, funky, popular, soul music that mirrored a comparable movement within the jazz scene.

JAZZ BY ASSOCIATION

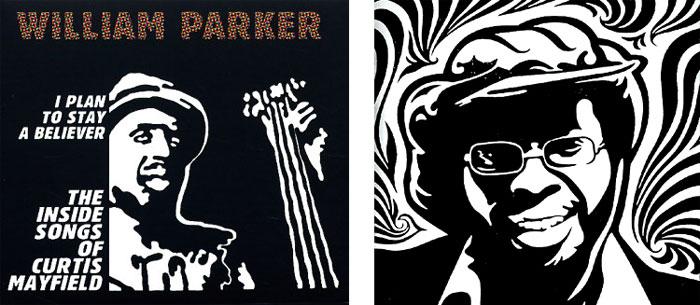

What is featured here is not Curtis Mayfield so much as the influence his music has had on jazz as demonstrated specifically by two jazz releases: I Plan to Stay a Believer: The Inside Songs of Curtis Mayfield (2010) by William Parker and Impressions of Curtis Mayfield (2012)by Jazz Soul Seven. Both releases take opposite directions on a journey exploring the possibilities and restrictions of Mayfield’s music as it is applied to jazz. While neither was a candidate for MUZAK, both bands fell short from expectations.

In 2010 American free jazz double bassist, poet, and composer, William Parker released the CD set:

I Plan to Stay a Believer: The Inside Songs of Curtis Mayfield. In so many words some critics said this is not all jazz, and others said this is not jazz at all. I have to agree with all. This is a compilation taken from various concerts at which the Curtis Mayfield songs were played, with big differences of approach and quality. The record starts very strong, with Leena Conquest on vocals, and the “established” William Parker band: William Parker on bass, Hamid Drake on drums, Lafayette Gilchrist on piano, Lewis Barnes on trumpet, Darryl Foster on tenor & soprano sax, Sabir Mateen on alto & tenor sax. In short, the band we know and have come to love. The playing and the singing are exceptional, full of funky soul, and energetic drive with grand soloing. Sorry to say it only lasts for two tracks. Amiri Baraka is heard on six tracks, talking rather than singing and on those pieces the recording quality is bad, with the musicians being reduced to a supporting background role. Finally it spirals downward into a sort of artificial gospel when the children’s choirs from either France or the New Life Tabernacle Generation of Praise in New York take the lead vocals, with the band pushed further into the background. Too bad the results were inconsistent because Parker had a great idea and you have to give him credit for attempting this endeavor.

For these “covers”, Parker is putting in action his belief that, “every song written or improvised has an inside song that lives in the shadows, in-between the sounds and silences and behind the words, pulsating, waiting to be reborn as a new song.” His band’s interpretations of these songs leave the basic melodies, but seemingly recast them as a harsher reality than what Mayfield initially recorded. To bring the point home, Leena Conquest occasionally updated the lyrics and her singing is sometimes supplemented by Baraka shouting about the indignation ever present in the world around us. When these new performances were recorded, the original lyrics depicting the frustrations with racial inequalities and Nixon in, “If There’s A Hell Below”, have been replaced with George W. Bush and a sharp anger at the war in Iraq. It would be interesting get Mayfield’s take on this if he were alive today. Regardless, I guess the spoken vocals seem like something I had not bargained for when first looking at the price on the package. Like buying lunch that includes free extra ketchup and special sauce that I did not order or want in the first place, covering the true taste of my hamburger. In fact the spoken vocals did little in comparison to the original mild, fluid, yet insistent vocals Mayfield was known for. The female version vocals were a nice touch and was never too domineering especially being stretched out over the 2 discs, which consisted of only eleven tracks sometimes reaching fifteen to twenty minutes due to the amazing improvised instrumentals.

Parker never intended to do “covers” of Mayfield’s songs, and firmly states so in his liner notes. Instead, he wanted to “present a full spectrum story that would be in tune with the original political and social message laid out by Curtis”.

In an interview (courtesy of destination-out.com, William Parker, and AUM Fidelity) Parker himself provides some illuminating details:

“This is the first project, in my 30-year career, that I have devoted to the music of someone else. It grew out of ‘Sitting by the Window’, a homage to Curtis Mayfield that I wrote for my band, In Order To Survive. The current project develops this inspiration while trying to call upon the spirit in which Curtis Mayfield wrote his songs. We are trying to let that spirit find its voice today through musicians who not only know Mayfield’s songs, but more importantly, know themselves. They are familiar with the language of a music that includes Curtis Mayfield as well as Sun Ra.

I grew up listening to Smokey Robinson, The Temptations, Martha and The Vandellas, Gladys Knight and The Pips, and Curtis Mayfield and The Impressions. In my mind, their music was not separate from Marian Anderson, Count Basie, Coleman Hawkins, Ben Webster, Don Byas, Sarah Vaughn, Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry, Cecil Taylor, Bill Dixon, and Louis Armstrong. All this music is part of an African American tradition that comes out of the blues. The roots of the jazz known as avant-garde are also in the blues, the field holler, and the church. Avoiding artificial separations is the key to understanding the true nature of the music. All these artists ultimately speak using this reservoir of sounds and colors that we can use to paint our own music.”

“The music that passed through the life and work of Curtis Mayfield cannot be duplicated. The question becomes, how can it then continue? I also ask myself this question in connection to Duke Ellington or Thelonious Monk. It always seemed to me that when Ellington died, the music physically died with him. We were left orphaned, with just the recorded part of his work and all these notes on paper, but that is not the reality. Once you realize this truth, you can find a different way to proceed to re-create the songs. Paradoxically, you can only find a way to play the music by initially affirming that it cannot be done.”

“Curtis Mayfield was a prophet, a preacher, a revolutionary, a humanist, and a griot (West African historian, storyteller, praise singer, poet and musician ). He took the music to its most essential level in the America of his day. If you had ears to hear, you knew that Curtis was a man with a positive message – a message that was going to help you to survive. He was in the foreground, always in the breach, both soft and powerful at the same time. For these reasons, his music still resounds in my heart.”

William Parker excels at the conception of a dense, hyperactive, barrage of sound, birthed from the inherent harmonic properties of his bass instrument. At his foundation, he is a textural player. Lyricism plays a secondary role in his work, with or without the bow. Parker’s pizzicato style is overwhelmingly percussive, in purpose and effect. Though he does, to an extent, serve as a harmonic anchor in his groups, his more important role is as a source of energy. He drives his band like a hammer drives a nail.

Parker was born in the Bronx and grew up in New York City. He was not formally trained as a classical player, though he did study with Jimmy Garrison, Richard Davis, and Wilbur Ware and learned the traditional craft. Very early in his career he formed an association with Cecil Taylor after he played Carnegie Hall with the pianist in the early ’70s. They recorded eleven albums together. Parker released his first album as leader in 1979. In the early ’90s, the direct musical heirs of Cecil Taylor, Albert Ayler, and Ornette Coleman were mostly ignored by New York jazz critics. Instead they favored the hard bop revivalists who dominated the major recording labels. Therefore, the public visibility of musicians devoted to a liberated “energy music” aesthetic remained minimal. Despite its low profile, however, free jazz was kept alive by a fairly large group of Lower East Side musicians, many of whom congregated around the music’s pre-eminent bassist, William Parker. Parker was the scene’s major catalyst for musical activity. He has long been a member of saxophonist David S. Ware’s quartet as well as the various groups led by Peter Brötzmann. It is plain to see that Parker’s Mayfield project seems out of step with his other work. Parker is interpreting someone else’s music that doesn’t jive with the avant-garde jazz Parker is closely associated with. These live shows give a more versatile side to Parker and band with danceable rhythms and hard grooves mixed with enough raucous improvisational soloing to please the usual avant-garde enthusiast. Maybe this attempt to redefine something so dissimilar makes I Plan To Stay A Believer a little too diverse, too beyond the grasp of some listeners, but that very diversity and mixture highlights all the inspiring, uninhibited, insightful, work that Curtis Mayfield left for us to grapple with.

Parker was born in the Bronx and grew up in New York City. He was not formally trained as a classical player, though he did study with Jimmy Garrison, Richard Davis, and Wilbur Ware and learned the traditional craft. Very early in his career he formed an association with Cecil Taylor after he played Carnegie Hall with the pianist in the early ’70s. They recorded eleven albums together. Parker released his first album as leader in 1979. In the early ’90s, the direct musical heirs of Cecil Taylor, Albert Ayler, and Ornette Coleman were mostly ignored by New York jazz critics. Instead they favored the hard bop revivalists who dominated the major recording labels. Therefore, the public visibility of musicians devoted to a liberated “energy music” aesthetic remained minimal. Despite its low profile, however, free jazz was kept alive by a fairly large group of Lower East Side musicians, many of whom congregated around the music’s pre-eminent bassist, William Parker. Parker was the scene’s major catalyst for musical activity. He has long been a member of saxophonist David S. Ware’s quartet as well as the various groups led by Peter Brötzmann. It is plain to see that Parker’s Mayfield project seems out of step with his other work. Parker is interpreting someone else’s music that doesn’t jive with the avant-garde jazz Parker is closely associated with. These live shows give a more versatile side to Parker and band with danceable rhythms and hard grooves mixed with enough raucous improvisational soloing to please the usual avant-garde enthusiast. Maybe this attempt to redefine something so dissimilar makes I Plan To Stay A Believer a little too diverse, too beyond the grasp of some listeners, but that very diversity and mixture highlights all the inspiring, uninhibited, insightful, work that Curtis Mayfield left for us to grapple with.

An ensemble of talented seasoned jazz musicians called Jazz Soul Seven has collaborated on a tribute, entitled Impressions Of Curtis Mayfield. This is a group that has a remarkable jazz pedigree lineage both as leaders from their own bands and session work with other musicians too numerous to name. This all-star lineup includes saxophonist Ernie Watts (Quincy Jones, Gerald Wilson, Charlie Haden and The Rolling Stones), guitarist Phil Upchurch (Dizzy Gillespie, Woody Herman, Stan Getz,) Upchurch together with Pete Cosey played guitar on the most controversial album ever released from Muddy Waters. Upchurch even sessioned for Mayfield. There are two pianists, Russ Ferrante (Yellowjackets fame), and Bob Hurst (Branford Marsalis), trumpeter Wallace Roney (Art Blakey, Tony Williams), drummer Terri Lyne Carrington (Wayne Shorter, Dianne Reeves, John Scofield), and another veteran who recorded with Mayfield, percussionist Master Henry Gibson. This recording in many ways is everything I Plan To Stay A Believer is not. It is not live. It is a studio effort. The sound quality is impeccable. There are no vocals. This release is performed by musicians that work in the bop and post bop genre of straight ahead jazz while William Parker and his band are mostly known in the free jazz circles.

An ensemble of talented seasoned jazz musicians called Jazz Soul Seven has collaborated on a tribute, entitled Impressions Of Curtis Mayfield. This is a group that has a remarkable jazz pedigree lineage both as leaders from their own bands and session work with other musicians too numerous to name. This all-star lineup includes saxophonist Ernie Watts (Quincy Jones, Gerald Wilson, Charlie Haden and The Rolling Stones), guitarist Phil Upchurch (Dizzy Gillespie, Woody Herman, Stan Getz,) Upchurch together with Pete Cosey played guitar on the most controversial album ever released from Muddy Waters. Upchurch even sessioned for Mayfield. There are two pianists, Russ Ferrante (Yellowjackets fame), and Bob Hurst (Branford Marsalis), trumpeter Wallace Roney (Art Blakey, Tony Williams), drummer Terri Lyne Carrington (Wayne Shorter, Dianne Reeves, John Scofield), and another veteran who recorded with Mayfield, percussionist Master Henry Gibson. This recording in many ways is everything I Plan To Stay A Believer is not. It is not live. It is a studio effort. The sound quality is impeccable. There are no vocals. This release is performed by musicians that work in the bop and post bop genre of straight ahead jazz while William Parker and his band are mostly known in the free jazz circles.

Impressions Of Curtis Mayfield is reminiscent of the 1995 release The New Standard by Herbie Hancock, who incidentally remade the Mayfield song “Future Shock” as a title cut to one of his most commercially successful albums. Hancock has the uncanny capability of taking a thread from someone else’s song and weaving his own tapestry from that one thread. The music by the Jazz Soul Seven is that good; at times almost too perfect and at other times a little stringent almost inflexible. My main complaint is that the solos are not long enough nor as free and out of control as perhaps they could be. Perhaps my ears feel tainted having heard the William Parker versions.

There are several interesting arrangements like “I’m So Proud”, but in typical order as with most of the other songs, it fades out just when you would expect somersault solos to come blaring out now that the band has warmed up. These musicians are almost too proper, careful not to tread on one another’s effort. “It’s All Right” has a harmonic, Ramsey Lewis-type piano line and Upchurch implements a fluent guitar solo that brings to mind the work of Wes Montgomery or George Benson. I like them but I wanted to hear Russ Ferrante and Phil Upchurch. Where did they go? For some reason working with these cover songs, the musicians would slip into mimicking perhaps one of their great personal influences. Watts and Rooney did manage to keep their Coltrane and Davis imitation in check only allowing it to surface now and then. The choice of songs strenuously attempted to cover the career of Curtis Mayfield as well as 12 songs can cover a lifetime as opposed to concentrating largely on just the hits. The absence of “Pusher Man” was sorely felt.

“Check Out Your Mind”, “Keep On Pushing”, and “Freddie’s Dead” are as about as perfect an arrangement and execution as possible. It does not get any better. I must say job well done. However, the song “People Get Ready” was pale in comparison and almost as lame as the Rod Stewart /Jeff Beck version. “Amen” was the worst milk toast rendition that anyone would ever hope to hear especially if you have ever experienced that song in a tent revival atmosphere with Pentecostal enthusiasm. It is one of those simple songs aching to have a transplant of instrumental improvisational solos in the middle, beginning, or end; little difference where because the song would always be recognized after a return to the simple melody. To be blunt regarding this release, when it was good, it was very good; when it was bad it should have been better, much better, because the caliber of these veteran musicians could have delivered much more heart and soul felt interpretations of the songs from a man who has been regarded a musical genius.

The jazz interpretations of Curtis Mayfield are worth hearing if for no other reason but to eliminate the monotonous layers of fluff, finally exposing the song writing skills that were all but buried. The plucking harps, and syrupy sweet violins found in Mayfield’s music were usually an industry standard for most soul music from that era. It probably was an attempt by the record companies to land a pop hit. Unless the artists come out and bites the hand that feeds/chokes them, it is uncertain who controls the creative puppet strings. Curtis Mayfield, Marvin Gaye, Isaac Hayes, Al Green, were all victims of studio recording filler that was supposed to enhance the original sound. Many jazz musicians suffered from the same epidemic of blankets of saccharine coated orchestration, punctuating pitch – perfect chorus singers, and wimpy, sniveling horn sections that sounded like they were recorded from tiny little brass instruments that could fit in the palm of your hand. For those who find it difficult to tolerate the high fructose mixing board magic, the Curtis Mayfield original recordings are now available on CD which often includes additional demos or versions of the song before all the additives rendered it indigestible. You can actually hear Mayfield singing with just bass and percussion accompanying his guitar work. Very nice. That is probably why the CURTIS/ LIVE has remained so popular and highly sought after. It is an excellent quality recording of some of his most poignant material stripped down to a simple band in a comfortable small club atmosphere. YOW !!!

The jazz interpretations of Curtis Mayfield are worth hearing if for no other reason but to eliminate the monotonous layers of fluff, finally exposing the song writing skills that were all but buried. The plucking harps, and syrupy sweet violins found in Mayfield’s music were usually an industry standard for most soul music from that era. It probably was an attempt by the record companies to land a pop hit. Unless the artists come out and bites the hand that feeds/chokes them, it is uncertain who controls the creative puppet strings. Curtis Mayfield, Marvin Gaye, Isaac Hayes, Al Green, were all victims of studio recording filler that was supposed to enhance the original sound. Many jazz musicians suffered from the same epidemic of blankets of saccharine coated orchestration, punctuating pitch – perfect chorus singers, and wimpy, sniveling horn sections that sounded like they were recorded from tiny little brass instruments that could fit in the palm of your hand. For those who find it difficult to tolerate the high fructose mixing board magic, the Curtis Mayfield original recordings are now available on CD which often includes additional demos or versions of the song before all the additives rendered it indigestible. You can actually hear Mayfield singing with just bass and percussion accompanying his guitar work. Very nice. That is probably why the CURTIS/ LIVE has remained so popular and highly sought after. It is an excellent quality recording of some of his most poignant material stripped down to a simple band in a comfortable small club atmosphere. YOW !!!

Bibliography and resources:

- destination-out.com

- Jazz Soul Seven: Impressions of Curtis Mayfield (2012) by C. Michael Bailey, Published: May 17, 2012

- allaboutjazz.com

- audaud.com

- downbeat.com